Regresar

Regresar

30 septiembre, 2015

4srealestate

Cities used to grow by accident. Sure, the location usually made sense—someplace defensible, on a hill or an island, or somewhere near an extractable resource or the confluence of two transport routes. But what happened next was ad hoc. The people who worked in the fort or the mines or the port or the warehouses needed places to eat, to sleep, to worship. Infrastructure threaded through the hustle and bustle—water, sewage, roads, trolleys, gas, electricity—in vast networks of improvisation. You can find planned exceptions: Alexandria, Roman colonial towns, certain districts in major Chinese cities, Haussmann’s Paris. But for the most part it was happenstance, luck, and layering the new on top of the old.

At least, that’s the way things worked for most of human history. But around the second decade of the 20th century, things changed. Cities started to happen on purpose. Beginning with New York City’s zoning laws in 1916, development began to occur by commission, not omission. Laws and regulations dictated the shape of the envelope. Functional decisions determined aesthetic outcomes—not always for the best.

So let’s jump to now: A century, plus or minus, after human beings started putting their minds toward designing cities as a whole, things are getting good. High tech materials, sensor networks, new science, and better data are all letting architects, designers, and planners work smarter and more precisely. Cities are getting more environmentally sound, more fun, and more beautiful. And just in time, because today more human beings live in cities than not.

In this year’s design issue, we’re telling the stories of some of those projects, from the detail of a new streetlight to a sacred city in flux, from masterful museums to infrastructure made for bikes (and the algorithms that run it all). The cities of tomorrow might still self-assemble haltingly, but done right, the process won’t be accidental. A city shouldn’t just happen anymore. Every block, every building, every brick represents innumerable decisions. Decide well, and cities are magic. —Adam Rogers

Los Angeles is retrofitting 4,500 miles of orange-yellow sodium-vapor streetlights with a moonlight-hued matrix of light-emitting diodes. Roads will look brighter, but they’ll also be more connected. Every energy-efficient lamp will link wirelessly to the Bureau of Street Lighting, letting headquarters know if it is on, off, broken, etc. And in the future? Lights that change in response to what’s going on around them. They might blink if a police car or ambulance is on its way or brighten for pedestrians after a ball game. While other cities around the world use LEDs to save money and add splashes of color and emphasis, LA plans to build a network that does more than show what’s happening right in front of you. It tells you something about the entire city. —Adam Rogers

More than 70 million people passed through Los Angeles International Airport in 2014—a jet-lagged gauntlet of wheely bags and neck pillows. Now LAX is getting an upgrade, a more than $8 billion overhaul of everything from concession areas to moving walkways. Delta kicked in $229 million to rework its Terminal 5. The revamp includes Delta One, a sort of airport within the airport that caters to celebrities and the wealthy. It presages a future where airports are less ad hoc, better organized, and not so dehumanizing.

On arrival, a curbside attendant checks your name, velvet-rope-style. Once you’re checked in, it’s off to a swanky lounge, one of the most private spaces in the terminal. When it’s time to board, Delta escorts take you up a private elevator and down a private corridor to the front of the line at a priority security checkpoint.

On the way home you can opt for an express exit with Delta’s VIP Select service. You’re chaperoned to the tarmac, then a hybrid Porsche zooms you across the airfield and onto Century Boulevard where, presumably, your driver will be waiting. —Nate Berg

The palm trees along Hollywood Boulevard may be iconic, but native to LA they are not. And as California staggers through drought, landscape architects are replacing imported plants and thirsty turf with native and drought-resistant flora. This new look—call it California Dry—is all about getting creative with textures and shapes. —Liz Stinson

To experience Hopscotch, an opera set in 24 limousines and SUVs driving around downtown LA, the audience will sit knee-to-knee with singers and musicians. Over the course of the show’s run in October and November, the cars will drive three routes, tracking a story of the search for a lost love. Actors and dancers with wireless mics will perform on the sidewalk and in cars passing by, mixing with the ballet of everyday city life.

“LA feels like the central character,” says Yuval Sharon, artistic director of the Industry, the opera company behind the production. Audience members—just 96 per performance—will also leave the cars and enter buildings and public spaces, with each walk or ride telling one of 36 chapters. You might want to attend more than once—any given audience member will see only eight chapters. —Nate Berg

A view of the entrance side of the museum. PHOTO BY:JOE MCKENDRY

Shanghai has exploded skyward in recent years, throwing up rank upon rank of bristling skyscrapers. Then there’s the new Shanghai Natural History Museum. Set in a park near the Pudong financial district, the building spirals down, into the earth, like an excavation of the city’s pre-urban roots. A central courtyard (shown above) inspired by the water gardens of Suzhou is a reminder of the value that ancient Chinese culture placed on natural beauty. Around it, a honeycombed glass wall, evoking the cell structure of plants, fills the interior with sunlight.

Architect Ralph Johnson of Perkins+Will says the shape of the building was inspired by the nautilus shell, but it’s also for traffic control: Chinese museums are often thronged, and the descending ramps steer crowds through a chronological tour of life on Earth. On the way, they encounter some 11,000 specimens—including a towering Mamenchisaurus skeleton and later fauna that once thrived in Shanghai’s vanishing wetlands. There’s plenty of forward-looking tech too—like green climate and water systems. (That courtyard pool helps cool the building.) It’s a thoroughly modern museum that embraces Shanghai’s exuberant futurism while reminding its inhabitants of where we all came from. —Victoria Tang

Medellín is nestled in a valley high in the Andes, and many of the city’s poorest residents live in comunas they built on the steep slopes. During the ’90s, drug gangs and guerrilla fighters controlled the narrow streets. As the violence waned and people started venturing out, they came up against another challenge: It was really hard to get anywhere.

To knit together the fractured city, then-mayor Luis Pérez proposed a novel solution: cable cars. Rather than having to pick their way down perilous hillsides, people could hop in a gondola and soar to a metro station. The first Metrocable line opened in 2004 and was quickly followed by others.

“The genius of the Metrocable is that it actually serves the poor and integrates them into the city, gives them access to jobs and other opportunities,” says Julio Dávila, a Colombian urban planner at University College London. “Nobody had ever done that before.” As people of all classes started using the cars to visit “bad” neighborhoods, they became invested in their city’s fate, heralding a decade of some of the world’s most innovative urban planning. —Lizzie Wade

Exterior design of the Biblioteca Espana. PHOTO BY:JOE MCKENDRY

The Metrocable succeeded in connecting Medellín’s poorest neighborhoods to the rest of the city, but that wasn’t enough for Alejandro Echeverri. As the city’s director of urban projects from 2004 to 2008, the architect threw himself into tackling some of Medellín’s most challenging urban problems. His secret weapon? Beautiful design. But his efforts weren’t aimed at the rich—Echeverri insisted on working in the same low-income areas the cable cars had opened up. “A good building, a well-designed space, a dignified public transit system, a quality cultural event—these all work on a psychological level to generate a feeling that you are included in the city,” he says. That philosophy guided the design of five libraries sprinkled throughout Medellín, all surrounded by beautiful greenery. These “library-parks” were among the first safe public spaces many neighborhoods had ever seen. (After Echeverri’s tenure as director ended, the city built five more.)

But Echeverri knew he couldn’t just throw up nice buildings and expect life to improve. His department went street by street, planting trees and replacing crumbling schools. “One of the keys to Medellín’s success is that these aren’t isolated projects,” Echeverri says. They’re all woven together—cocreations, as he calls them—with the communities that use them every day. —Lizzie Wade

Spray paint in hand, Daniel Felipe Quiceno, aka Perrograff, aims at the wall. “The lines of your signature need to be well defined,” he tells the group gathered around him for a lesson in graffiti. With a practiced flourish, he creates a sharp swoop of blue. Then he hands out aerosol cans so his students can try making their own mark on Medellín.

Since Perrograff started the Graffitour three years ago, it has brought hundreds of visitors to the once-neglected streets of Comuna 13. That’s where he grew up, amid terrible violence. To fight back, his cohort began transforming run-down corners of their town by covering them in murals that illustrate Comuna 13’s history and that memorialize murdered friends; they also started planting community gardens.

Grassroots efforts like the Graffitour have been a vital part of Medellín’s transformation, says Jota Samper, an urban planner who grew up there and now teaches at MIT. The Metrocable and library-parks are great, but “what makes these projects amazing are the neighborhoods where they are located,” he says. For his part, Perrograff hopes his community work will soon go beyond two dimensions. After years of painting flat surfaces, he’s studying to be an architect. —Lizzie Wade

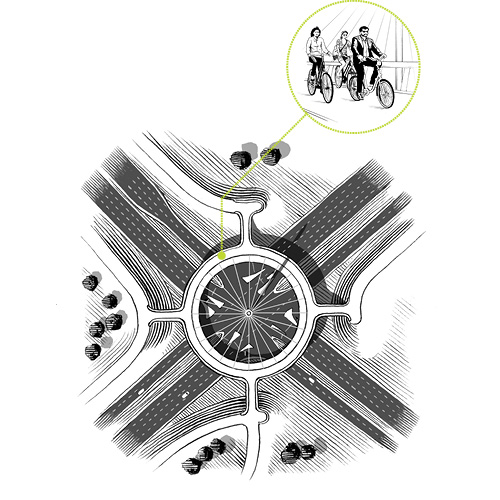

An overhead view of Eindhoven’s Hovenring. PHOTO BY:JOE MCKENDRY

Eindhoven was a sleepy provincial town when a family named Philips began making lightbulbs there in 1891. Today it’s a vibrant technology and research hub, where many workers commute in from sprawling suburbs. That makes for some busy intersections that aren’t exactly bicycle-friendly. So as part of a planned network of dedicated bike roads, Eindhoven asked design firm ipv Delft to come up with a way for cyclists to fly over the stop-and-go. Completed in 2012, the $8 million Hovenring is the rare piece of cycling infrastructure that isn’t an afterthought—a green strip alongside parked cars or a bike symbol painted on a bus lane. The 1,000-ton steel deck is suspended by 24 cables from a towering space needle. Dressed up in LEDs, it looks ready to spin up and away into the northern sky. The city even lowered the roadbed below to keep the approach ramps at a nice, easy slope. The Hovenring is a joy for thousands of commuters who now pedal into and out of Eindhoven every day—and an emphatic statement by a city that knows where it’s going. —Alex Davies

For five days every year, the population of Saudi Arabia increases by 3 million. That’s when Muslims visit Mecca for one of the religion’s most sacred rites: the hajj. Most cities aren’t built with that kind of surge capacity. And as the tragic stampede at this year’s gathering showed, at a certain density those crowds can become dangerous. So the Saudis have, over the years, turned to a series of the world’s best architects and designers to try to keep millions of pilgrims safe, healthy, awed, and (a few of them) very, very comfortable—while honoring the tenets of Islam. The result is a city of carefully regulated experiences, with more work yet to be done. —Tim De Chant

Inspired by traditional Bedouin tents, the 2.8-million-square-foot Hajj Terminal at King Abdulaziz International Airport has two massive cable-stayed, Teflon-coated fiberglass roofs. Passengers grab their luggage in the climate-controlled section; natural ventilation in the open-air waiting area keeps temperatures around 80 degrees Fahrenheit, even while they hit a searing 120 outside. There pilgrims wait—sometimes up to 36 hours—for their ride to Mecca, 43 miles to the east. —Tim De Chant

The $20 billion-plus the Saudi government has spent on mosque improvements will solve at least one unholy problem: 600 tons of trash a day. It’ll disappear into 400 openings and get sucked at 40 mph through an underground network of pneumatic tubes to a station more than a mile away, where trucks will take it to a landfill. —Juliette Spertus

The Masjid al-Haram, the Great Mosque of Mecca, is an ever-expanding house of worship built around the holiest shrine in all of Islam—the cloth-draped granite cube known as the Kaaba. Pilgrims walk seven times counterclockwise around the Kaaba twice on their hajj trip, and in recent years crowds have been so thick that they’ve forced people onto the mosque’s roof. Architects from the firm Gensler took a cue from those rooftop pilgrims and proposed a series of eight-sided platforms surrounding the Kaaba. Upgrading the mosque has been a delicate balancing act, says Bill Hooper, head of Gensler’s transportation practice. “We needed to keep them as close in to the Kaaba as we could but not compromise the emotional experience.” The solution, Hooper says, will improve traffic flow, double capacity, and maintain sight lines. Buildings around the Masjid al-Haram have been received less fondly, though. Abraj Al-Bait is the least-likely second-tallest building in the world, dominated by a Big Ben-like central clock tower that looms 1,972 feet above the mosque. The hotel is augmented by a light show at night. —Tim De Chant

Planned for completion in 2017, the Abraj Kudai will be the biggest hotel in the world—12 towers, 10,000 hotel rooms, 70 restaurants, four helipads, a shopping mall, and a bus station. Five floors are said to be reserved for the exclusive use of the Saudi royal family; the merely wealthy will have to make do with standard accommodations. It’s a decidedly odd, neoclassic addition to the site. —Tim De Chant

Most pilgrims spend nights in the Mina Valley—the hajj’s midpoint—in a vast tent city. For decades the sandy plain was crammed with simple cotton tents, but a deadly fire in 1997 sent the Saudi government searching for a durable fireproof replacement. Now an extensive network of permanent hydrants helps protect more than 100,000 air-conditioned, semipermanent structures of Teflon-coated fiberglass, each ranging from 250 to 850 square feet. And since close quarters can also aid the spread of illness, Mina has dedicated hospitals and ambulances too. Safety is still an issue here, though—it was in Mina that a stampede killed at least 700 people during this year’s Hajj. —Tim De Chant

Pilgrims come to the Jamarat Bridge on the third day of the hajj for the Stoning of the Devil—to throw seven pebbles at each of the three jamarat, pillars representing the three times Abraham refused the devil’s challenges. The bridge was the site of several stampedes in the ’00s, one of the most dangerous parts of the crowded pilgrimage, before architects built the area around the jamarat into a long five-level bridge. Now people have better access to the pillars, and a handful of exit ramps can now help quickly clear the structure, though the area still gets crammed with people. —Tim De Chant

Most people get around Nairobi in minibuses. Run by various entrepreneurs, the vehicles—called matatus—are cheap, plentiful, and known for loud music and sparkly disco balls. But schedules in this ad hoc network change at will, and finding the right route or stop is a crapshoot—a wrong decision can add hours to your trip.

Enter a group of researchers and designers called Digital Matatus. It tasked local university students with riding the buses and using a smartphone app to track the routes and stops. When Digital Matatus released its subway-style map of more than 100 routes and major stops last year, people snatched them up. “Women, especially, said, ‘This is valuable, because at night I don’t want to get on the wrong matatu where I don’t feel safe,’” says Jacqueline Klopp, one of the project leads.

But it gets even cooler: A few months ago, the Nairobi matatus became the first informal transit system on Google Maps. The move to a global platform legitimizes the zippy little vehicles and shows other cities how they too might harness these networks. Ultimately the goal is to strengthen the matatu system even further—fingers crossed it will still include a disco ball or two. —Shara Tonn

Step into someone’s “office” these days and it might not look like an office at all. People are working out of garages, cafés, the park. But for many startups and remote teams, it’s still important to have a space to call their own. Enter WeWork, the biggest name in coworking. Founded in 2010, the company operates 44 coworking spots around the world. Not just open-floor plans and long desks, mind you—these are full-service environments, with well-designed communal areas, bright private rooms, and (of course) bottomless coffee. “Natural light and openness are the foundation,” says WeWork cofounder Miguel McKelvey. “Beyond that, we try to bring a sort of eclectic spontaneity.” It’s working. The company is valued at $10 billion and hosts thousands of workers. We visited its Golden Gate location, where nine people showed us around their—well, their space. —Julia Greenberg

Emirates Road used to be a nightmare. The only way to get off the then-six-lane highway and onto intersecting roads was a congested roundabout that required drivers to stop before merging into traffic. Finally, in 2006, city officials decided to restructure parts of the highway, starting with the dreaded roundabout. ¶ Rather than use a cloverleaf—the century-old grandfather of congestion remedies—they opted for a more modern configuration known as a turbine interchange. Devised in the UK in the 1960s, it allows drivers coming from four directions to engage in any turn or change of direction without slowing or weaving into traffic. Unlike stacked interchanges, which can involve four, five, or even six tiers of elevated highways, turbines require fewer levels, so the overall materials cost is much lower. “The turbine is high-speed and high-capacity,” says Gilbert Chlewicki, director of Advanced Transportation Solutions, a civil-engineering consultancy. “It’s the most efficient and practical solution.”

Turbines use up a lot of land, but that’s not a problem in sprawling Dubai. So after two years and $111 million, the Arabian Ranches Interchange opened in 2008, connecting Emirates Road (now known as Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed Road) with the Umm Suqeim and Al Qudra roads. The turbine is nearly a third of a mile wide, with 11 bridges extending a total of 1.5 miles. That sounds like a tangle, but rotational symmetry makes for a consistent driving experience from all four approaches. And in a nation that seems to pride itself on ornate displays of wealth, the simplicity isn’t so hard on the eyes, either. —Ian Frisch

Source:Wired

**Inscríbete a nuestro newsletter para recibir contenido estratégico de desarrollo inmobiliario, haciendo click aquí. Si estás interesado en recibir información de nuestros servicios de conceptualización de proyectos y cursos, envíanos un correo a: capacitacion@grupo4s.com

#Industria Inmobiliaria

El mercado inmobiliario en México atraviesa un proceso de transformación...

enero 31, 2025

#Industria Inmobiliaria

El mercado inmobiliario en Latinoamérica está atravesando una transformación...

febrero 18, 2025

#Industria Inmobiliaria

El mercado inmobiliario de Guadalajara vive un momento de crecimiento acelerado...

octubre 31, 2024